Thomas Anshutz 1851-1912

Framed dimensions: 15 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches

Anshutz enrolled in The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1876, the year it reopened after a 5-year hiatus. He left the National Academy of Design in New York, where he had studied for two years, because of his dissatisfaction with the programmatic instruction. PAFA offered a larger course selection and most significantly emphasized life drawing classes and courses in anatomy. Thomas Eakins was largely responsible for this curriculum, and his influence at the Academy was profound during his tenure there. Eakins’s intense focus on anatomical study, dissection and life drawing made the Academy unique among American art schools. By the late 1870s and early 1880s, his pedagogy was nothing short of revolutionary. Eakins’s belief that good painting and sculpture were based on a sound understanding of anatomy, scientific accuracy, and careful observation became the cornerstone of his artistic philosophy and pedagogy. This approach initially dovetailed nicely with PAFA’s longstanding tradition of realism. Anshutz was deeply influenced by Eakins’s ideas and style, and subsequently became Eakins’s protégé, assisting him in anatomy dissections and then becoming chief demonstrator himself in 1880, when Eakins was named Professor of Drawing and Sculpture. In the fall of 1881, Anshutz was promoted to a full-time faculty member.

Like his teacher, Anshutz rejected what he saw as falseness and idealization in art. Randall Griffin in his book on Anshutz writes: “According to [Eakins and Anshutz], honesty and truth to one’s perceptions of nature constituted the only legitimate approach to art.” Both artists sought to capture mass and structure over meticulous detail. And while Anshutz never focused intensively on the nude as Eakins did, the human figure was central to his art from the 1870s onward. There is no question that Anshutz was indebted to Eakins’s influence; however, he never slavishly copied his work or recited his ideas by rote.

By the mid-1880s Anshutz had grown dissatisfied with some of Eakins’s theories and sought to broaden his artistic philosophy to include art for art’s sake aestheticism and Impressionism. Eakins was forced to resign from PAFA in 1886 because of his controversial approach to teaching, specifically removing a loincloth from a male model during an all-female life drawing class. Anshutz took over Eakins’s classes temporarily after his departure until Thomas Hovenden was hired full time.

In 1892 Anshutz enrolled in the Academie Julian, as he felt he needed to gain a better understanding of French painting. He was impressed by the caliber of students at the Academie, but he found the instruction style to be too informal. His time in Paris and exposure to different styles of painting, particularly the symbolism of the Nabis, was important to the evolution of Anshutz’s artistic style. He remained true to the academic rigor that he long championed, but his brushwork became more free and painterly.

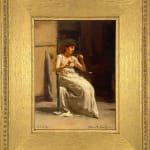

In Seated Woman, Anshutz showcases his technical dexterity and mastery of painting the human form. The sitter has poise and confidence. She is contemplative but not wistful. He has positioned her in a lovely setting that speaks to the cultural belief that a woman’s proper sphere evoked leisure, beauty, and aesthetic harmony. Unlike Anshutz’s earlier paintings that were more academic in style, Seated Woman is more painterly. Yet the carefully observed details and the tremendous skill he used to capture them are hallmarks of Anshutz’s creative powers.

There are only about 130 extant paintings by Anshutz. There is no question that he subjugated his own artistic career to his role as a teacher. His openness to new ideas coupled with a willingness to question accepted conventions made him an exceptional instructor and mentor during a time of great change. The art historian William Homer astutely identified Anshutz as an important bridge between Thomas Eakins and the group of restless PAFA students who would eventually help make up The Eight. Even though Anshutz’s own art remained deeply rooted in the academic tradition, his philosophy and teaching method acted as catalysts for the beginnings of early American Modernism.

Thomas Anshutz’s contribution as an artist is often overshadowed by his legacy as one of America’s great art instructors. He was an exceptional teacher, taking over for Thomas Eakins at PAFA, where he was particularly adept in identifying his student’s strengths and encouraging their individuality. Yet he was also a courageous artist, who used his extensive technical skill to great advantage and pushed himself to broaden his style and philosophy without regard for what was fashionable. In Seated Woman, Anshutz showcases his technical dexterity and mastery of painting the human form. He combines the carefully observed details with a painterly style and wonderful sense of light, making the painting an exceptional example of his best work.